If we are so inherently safe, why do we have accidents?

I was recently at a festival. It was a family friendly festival, where middle aged adults brought their children to have fun and enjoy live music at night and family friendly activities during the day. At the festival was an old-school funfair. The fair was modelled on Victorian technology and was in the main driven by steam engines. I love  Victorian engineering, because things are generally bigger, stronger and longer lasting than they perhaps need to be. I grew up in Cheshire just a stone’s throw from the Anderton boat lift. A marvel of Victorian engineering that essentially operated from 1875 when it was designed and built until the mid 1980’s when it was decided it needed a brush up. The lift still operates today.

Victorian engineering, because things are generally bigger, stronger and longer lasting than they perhaps need to be. I grew up in Cheshire just a stone’s throw from the Anderton boat lift. A marvel of Victorian engineering that essentially operated from 1875 when it was designed and built until the mid 1980’s when it was decided it needed a brush up. The lift still operates today.

This steam fair was just like that. Everything was beautifully made. Hardwood handrails, beautiful hand painted decoration and massively oversized metalwork. Yet, despite all this Victorian finery, a traditional health and safety professional would probably have had heart failure at some of the design features.

My daughter and I went on the steam yachts. Notwithstanding the ancient design, it was a thrill and a half. In order to get into the yacht we had to climb a staircase then step over a ten foot drop. No guard rail, no warning sign, no fall arrest system, yet we stepped across the gap into the yacht without incident. There was an attendant there to help, but we all managed it without assistance. Once on the wooden bench of the steam yacht, we were instructed to place our arms through the rear slats of the seat to stop us falling out when the yacht became vertical. No belts, braces or safety locks were used. Yet we all stayed in our seats, young and old, strong and frail. We even managed to step out of the yacht after our balancing system had been assaulted by the thrills and spills of the Victorian entertainment device.

This level of ‘risk’ was evident on many of the rides. Indeed, some of the rides were driven by Victorian steam engines. Belt driven with no guards, with belts at accessible height for adults and children. Yet no one got caught up in the drives. No one got injured while I was there, and I imagine no one has ever been injured by these devices of entertainment. Why is this? Well, they are not unsafe, we have common sense. We see the danger and we employ safe behaviour to address the risk. We do this because we have an innate desire to survive.

If we are so inherently safe, why do we have accidents?

It appears that I have asked this question twice. This is because it is such a big question! Why when we have such an inbuilt drive to preserve our own life do we have such terrible accidents?

The reason is a human one. There is some commonality among the causes of accidents. There is no one common cause, however, by understanding some of the frequent causes we can be better placed to prevent accidents from occurring.

Investigations teach us that there are a number of circumstances where accidents are more likely to occur. Believe it or not, it isn’t when the hazard is most severe. So lets look at some of the common causal themes. These are in no particular order.

Complacency – This one is probably no surprise. It is pretty important to be aware of though. I have a wood-fired pizza oven in my garden. When using it I am exceptionally careful, I make sure no one is standing nearby, I announce what I am doing, I take exceptional care when introducing the pizza to the oven. Yet when I see people in pizza restaurants they perform all this with little hesitation and caution. They are not necessarily complacent, but they certainly have less dynamic conception of the risks of the task. All it takes is for one small lapse of concentration and this almost automated task could end in an incident. This isn’t really a cause, but a contributory factor leading towards an error or violation.

Errors – Errors fall into two main categories. Skill based errors and mistakes. Skill based errors are slips of action or lapses of memory. Typically this is pressing the wrong button when you know which is the right one or perhaps forgetting or misremembering a well known fact. Mistakes can be rule based mistakes or knowledge based mistakes. Rule based mistakes are when a rule is applied from memory but perhaps in the wrong situation. For instance, a pilot is shown by a ground engineer that an annoying alarm can be reset by opening and closing a breaker. The pilot then repeats this action in flight and loses all hydraulic control. The pilot followed the rule he had learned without properly understanding the events. A knowledge based mistake is when the person does not have knowledge of a rule so they go back to first principals to work out what to do. However, their knowledge is flawed and the resultant outcome is a mistake.

Violations – These are when a rule or procedure is deliberately not followed. In my experience, many mistakes when investigated turn out to be violations. Violations fall into three categories, routine violations, where an individual always skips a step or fails to apply the rules. A situational violations is when an individual follows the rules except in certain circumstances. For instance, when on night shift they don’t bother doing a safety check because no one is watching, but during the day they always complete the check. An exceptional violation is when a rule isn’t followed because of the prevailing unfamiliar circumstance. For instance, if your child is badly injured, you may drive them to hospital even though you have had an alcoholic drink. There would be no other circumstance that would lead you to do this.

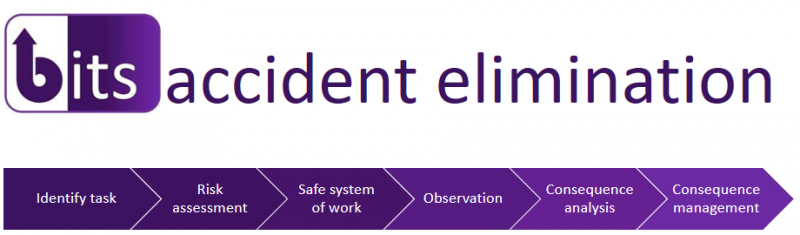

Armed with this knowledge, you now know what causes accidents to occur. So instead of focussing on the hazard and its severity, once we have a method and safe system of work in place, we should focus on the human and their behaviour. The only way to discover if you have violations and errors occurring that could lead to an accident is by skilled observation. Trained observers can record errors and violations before they lead to an accident. We can then act upon this learning. By using consequence analysis we can ascertain exactly why errors and violations are occurring. Once we establish this, we can introduce new consequences or remove existing ones to drive the correct behaviour.

No one sets out to have an accident, however human behaviour often means an accident is almost inevitable. It is our role to ensure that the accident never happens, through observation, consequence analysis and consequence management we can make this happen.