Maybe now is the time for change, unless you are reading this at night……

On April 28th 1988 the passengers on Aloha Airlines Flight 243 had what can only be described as a horrendous and terrifying experience on their short flight from Hilo to Honolulu. The plane was a Boeing 737, and was at the time one of the oldest 737s in service. Many of the passengers where regulars on this flight, which was just a short island hop. The flight was so short that the food was served during the post take off climb, and typically the seatbelt sign was never turned off as the plane spent so little time at cruising altitude. The cabin crew were very experienced, in fact one of the flight attendants, C.B.Lansing was Aloha airlines longest servicing cabin crew team member.

On April 28th 1988 the passengers on Aloha Airlines Flight 243 had what can only be described as a horrendous and terrifying experience on their short flight from Hilo to Honolulu. The plane was a Boeing 737, and was at the time one of the oldest 737s in service. Many of the passengers where regulars on this flight, which was just a short island hop. The flight was so short that the food was served during the post take off climb, and typically the seatbelt sign was never turned off as the plane spent so little time at cruising altitude. The cabin crew were very experienced, in fact one of the flight attendants, C.B.Lansing was Aloha airlines longest servicing cabin crew team member.

Everything on this flight was proceeding as normal until the plane reached its cruising altitude of 24,000ft. Just as the plane levelled out there was a catastrophic event. A large section of the fuselage simply blew away, immediately depressurising the cabin and exposing the passengers to conditions at 24,000 feet. Thankfully the passengers were still strapped in which was a main contributory factor to the survival of all passengers on this flight. Sadly, C.B.Lansing was sucked out of the plane during the depressurisation, making her the only fatality associated with this incident.

Despite the severe damage, the pilot was able to re-route to Maui and performed a safe landing. The ordeal for the passengers and crew was life changing. For the duration of the flight following the incident, they all feared death. They had no way of knowing whether the captain and first officer had survived. The emergency oxygen system had failed due to the damage and they were exposed to temperatures as low as -50 deg C.

The cabin crew were commended for their actions and the captain and first officer were recognised for handling the unprecedented emergency with great calmness and efficiency. So what caused this unusual and catastrophic failure?

Sometimes, even with hindsight we can miss what is in front of our face.

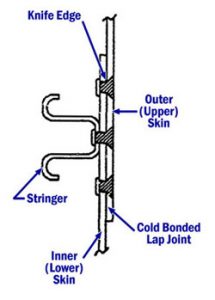

The Boeing shell is constructed of panels. Where these panels are joined there is a 3″ overlap. The overlapping panels are bonded and riveted together. The purpose of the bonding is such that loadings from the pressurisation of the cabin are carried by the bonding rather than the rivets. This prevents damage to the rivets and panels. There were known issues with the bonding which led to separation, corrosion and some instances where the bonding failed completely. As such, Boeing had issued additional maintenance instruction to airlines flying older models of this plane. Planes with this type of bonding (the use of which has long since been discontinued), required regular inspection for signs of surface cracking. The cracking would indicate that loadings were being carried by the rivets rather than the bonding, as such it could be inferred that the bonding had failed and required remedial action.

Instead of having each plane down for several weeks at a time to perform the checks, Aloha Airline opted to divide the recommended inspections into 52 weekly tasks. These planes were high cycle equipment, performing many short flights. This meant that they had low flying hours but a very high number of take offs and landings. This meant they were susceptible to high cyclic fatigue. Which in simple terms means that although their flying hours were low, their degradation due to use was likely to be higher than aircraft with higher flying hours. It also meant the planes were in the air during the day on scheduled flights and on the ground at night. This is where a significant human behavioural element introduces itself.

Instead of having each plane down for several weeks at a time to perform the checks, Aloha Airline opted to divide the recommended inspections into 52 weekly tasks. These planes were high cycle equipment, performing many short flights. This meant that they had low flying hours but a very high number of take offs and landings. This meant they were susceptible to high cyclic fatigue. Which in simple terms means that although their flying hours were low, their degradation due to use was likely to be higher than aircraft with higher flying hours. It also meant the planes were in the air during the day on scheduled flights and on the ground at night. This is where a significant human behavioural element introduces itself.

Aloha Airlines chose not to use radiographic or similar technology to search for cracks, instead they opted for visual inspection. Due to the duty of the aircraft these inspections were performed through the night. No defects or cracks requiring action were found or recorded on inspections of the aircraft on flight 243. It had it’s final pre-flight inspection in the early hours of the morning before take off. No problems were found.

One survivor of the flight reported that she had seen a worrying crack in the fuselage as she boarded the plane. It was a crack in the metalwork immediately above the rivets holding the panels together. She had been concerned about it, but decided not to mention it to staff as she assumed they knew what they were doing and would have been aware of it already. In fact no one was aware of the crack, and it indicated that the bonding had failed some time ago and the fuselage was in a very dangerous condition.

So the question one must ask is, how did a passenger, not skilled in aeronautical maintenance, notice a crack in the fuselage yet the skilled engineers and inspection teams had noticed nothing? The fact that inspections were performed at night was recognised as a contributory factor. Not only is the light source less effective for finding cracks, humans are significantly less efficient and function at much lower levels during night-time hours. Even those who are well acclimatised to night working are prone to the natural human phenomenon of circadian rhythms.

Circadian Rhythms

When working at night and sleeping during the day, working, eating and sleeping phases are changed. All mammals have a natural rhythmicity to bodily functions. We call these circadian rhythms, and humans are no different. As an example, under normal living conditions body temperature varies throughout the day. For humans it peaks in the late afternoon and is at its lowest point in the early hours of the morning. Other body metrics follow a similar pattern. Under experimental conditions, it is possible to reverse this cycle, but rotating shift workers usually only succeed in flattening the curves. So the best we can hope for is that a shift worker is operating at a slightly sub-optimal level all the time. However, many shift-workers fail to make this adjustment at all, and many drastically underperform during night-time hours.

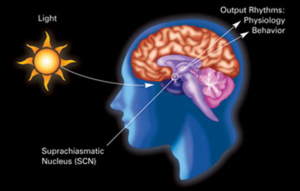

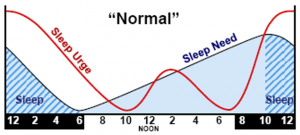

So why don’t we simply switch day for night and operate at the same levels? The answer is that our behaviour evolves quicker than our bodies. We choose to operate in ways that our body has not evolved to perform in. Our rhythms are determined by our interpretation of sunlight. If you’ve ever spent too long in a Las Vegas casino, you will be familiar with that disconcerting feeling you get when deprived of sunlight for a long time. You lose track of what time it is and start struggling with sleep patterns almost immediately. As a shift worker, you still get exposed to sunlight when on night shift. However, you are asking your body to sleep when your body has evolved to be wide awake and performing work. Then when you get to work, it is dark and the only light is artificial. Now your body is slowing things down in response to the light stimulus. The graph on the right shows how these rhythms play out. This is how we are ‘designed’ to operate. We sleep at night, reducing our sleep urge. As we are active through the day, our sleep need builds gradually. Our sleep urge generally follows our sleep need with a little wobble in the early afternoon. A wobble I am sure most of us are aware of. We usually address it with a Mars bar or strong coffee. As our sleep need peaks, our sleep urge tells us it is time to go to bed. Most human evolution took place before we had invented the clock. So, naturally our bodies evolved to use the sun as our stimulus for these rhythms.

builds gradually. Our sleep urge generally follows our sleep need with a little wobble in the early afternoon. A wobble I am sure most of us are aware of. We usually address it with a Mars bar or strong coffee. As our sleep need peaks, our sleep urge tells us it is time to go to bed. Most human evolution took place before we had invented the clock. So, naturally our bodies evolved to use the sun as our stimulus for these rhythms.

The impact we see on shift workers is significant. Health problems prevalent among shift-workers include sleep interruption, general fatigue, anxiety, depression, cardio vascular effects and some reported increases in gastrointestinal disorders. Also, from a safety point of view we have other concerns. The rhythms result in overall poorer levels of performance, particularly at night. We also see increased accident rates among shift-workers, especially at night.

We can’t really fight evolution, so how do we overcome the negative effects of these rhythms on shift work? There are some steps that can be taken to improve a human’s performance working at night. Achieving and maintaining a good level of physical fitness has a tremendous impact on our ability to work around our circadian rhythms. Rapid rotation of shift patterns helps too. Keeping the average working week well below 55 hours can help avoid fatigue impacting performance. Regular breaks in shift patterns give the body a chance to recover.

The work environment can be used to help overcome some of the issues associated with night working. Ensure the environment is pleasant and a stable temperature can be maintained. As light is our cue for performance levels, install natural light fittings to help convince your body that it’s time to be awake. Ensure night workers have access to good sources of food and drink. A chocolate vending machine and a kettle probably isn’t going to cut it! In general keeping well hydrated with water and avoiding the use of stimulants to provide energy bursts will help the body better overcome fatigue. Shift workers should have regular health checks from a medical professional who should be made aware that they are shift workers.

There are other steps a shift worker can take themselves in order to help improve their performance. Firstly they should recognise what sort of rhythm they are on. Although we all follow the same general rhythm we are not all perfectly synchronised with each other. Some of us perform better in the morning, others in the evening. People often use the terms larks and owls. We should all plan our days with this in mind. Know at which time you are best suited to perform detailed tasks and at which time you are more suited to easier tasks that require less attention.

Despite these effects of shift working, so many organisations schedule detailed, safety related work to be performed at night. Many organisations that operate safety rules with a permit to work system, hand over work requests to safety officers on night shift to prepare safety from the system requirements. Likewise, many safety inspections are performed in the night hours. As we saw in the Aloha Airlines incident above, sometimes the human effects of working at night mean that this is not the best time to perform detailed inspections.

A regular review of shift working practises can maximise the performance and health and safety of your team.

If you have 24 hour working in your business it often pays to review the cause for this. Sometimes production costs can be reduced by increasing staffing levels on days and closing down at night. Sometimes the only reason for a night shift is because there has always been one! In many situations, however, we cannot avoid night working. I used to work in the power industry, I am pretty sure that if we announced we were going to stop generating at night due to circadian rhythms, there would have been push back from critical service operators and the public in general. It is not always practical to shift your work to the daytime. So when night work is essential, here is a simple three point plan to minimise the risk to your business and people.

Get your workers fit for shift work – encourage good fitness levels among shift workers. Provide regular health checks. Encourage hydration, good diet and non-reliance on stimulants such as caffeine. Acknowledge that people who take up shift work late in life really struggle. Indeed older people are more negatively impacted by shift work. Build this into career plans where possible.

Get your shifts fit for your workers – have quick rotation of shift patterns, two weeks of days followed by two weeks of nights is not good for the body. Provide for long breaks in your shift pattern to allow recovery time. Do not overwork your employees, ensure average working weeks are less than 55 hours. If you have regular overtime, you should review your pattern and staffing levels. A positive attitude is a huge contributor to human performance. Allow your shift workers to get involved in the development of shift patterns and the design of their work environment. This enables them to have a more positive attitude towards work.

Fit your work into your shifts – it is critical to recognise the limitations of shift workers and the natural human tendency to drop performance at night. To this end, work should be organised such that safety critical tasks are not performed over night. Furthermore, during the night shift 3-4 am is often the lowest performance period. Ensure your workers have opportunity to schedule their work to allow for more routine tasks during this period.

The investigation into Flight 243 found that the Aloha Airline interpretation of the Boeing maintenance recommendation was inappropriate. Their methodology for inspection was found to be flawed. However, even when procedures are flawed, a competent, efficient, alert human on the end of the process can flag up problems and avert an accident. In this incident, it was found that technical staff regularly recorded the presence of cracks in 737 aeroplanes but never attributed any significance to this. In fact, following this event, related defects where found in almost every 737 in the Aloha fleet and 3 planes, including the one on flight 243 were scrapped as being beyond economic repair. It is not possible for us to accurately isolate the effect that circadian rhythms might have had in this incident. However, the fact that a passenger spotted a crack in the fuselage that an engineer working in the early hours of the morning had missed, suggests that human performance was effected by circadian rhythms.

Try and imagine being strapped to a seat, exposed to the elements at 24,000 feet travelling at 580 miles an hour. Now envisage what a serious incident at your place of work could look like. Then think how many safety critical tasks in your business are performed at night. Today might be time to take action.

RCA Source – Federal Aviation Administration.