Last week there was a tragic story in the media about a lady who was killed during a visit to the beach as a result of holding onto an airport fence. The incident happened at the famous Princess Juliana International Airport, which is just metres from the sea, on Sint Maarten. The beach is famous for being next door to an airport runway, with aeroplanes flying just above bathers as they come in to land. The airport runway attracts many visitors a year. Many of these visitors venture to the fence at the end of the runway and try to hold on against the force of the jet engines as the planes land. Police said the woman, 57, from New Zealand, had been doing just this before the force of the jet engines threw her backwards, causing serious injury, which later resulted in her death.

Last week there was a tragic story in the media about a lady who was killed during a visit to the beach as a result of holding onto an airport fence. The incident happened at the famous Princess Juliana International Airport, which is just metres from the sea, on Sint Maarten. The beach is famous for being next door to an airport runway, with aeroplanes flying just above bathers as they come in to land. The airport runway attracts many visitors a year. Many of these visitors venture to the fence at the end of the runway and try to hold on against the force of the jet engines as the planes land. Police said the woman, 57, from New Zealand, had been doing just this before the force of the jet engines threw her backwards, causing serious injury, which later resulted in her death.

Police perform regular patrols to remove people from the fence in order to avoid such incidents. There is signage around the area prohibiting access to the fence. However, hundreds of people visit the beach for this very experience. There are videos on YouTube of thrill-seekers being blown from the fence.

So when the risks are so great, why do people continue to partake in this pastime? The risk is fairly evident, we have most of us seen the videos on social media and the signage is pretty clear. If I showed you a video two weeks ago, and asked if you would hold onto the fence for a thrill, maybe you would say yes. After reading the news of the recent tragedy, would your answer change?

In 1995 there was a very high profile tragic incident involving illegal drugs. Leah Betts, a teenager died as a result of taking ecstasy and drinking seven litres of water in 90 minutes. This happened just days after her eighteenth birthday. The event resulted in lots of publicity and a heavily resourced police investigation into the supply of the tablet. The public response was phenomenal with calls for stronger penalties for drug dealers, crack downs on doormen at night clubs, even legalisation and control of the supply of ecstasy. Understandably concerned parents focussed their attention on protecting their children from a similar fate. However, did they focus time and effort on the right risk? Was accidental death from a bad batch of ecstasy followed by over hydration the biggest risk facing British teenagers that year? In fact if you had a teenage child in 1995 they were twice as likely to die from chickenpox as an ecstasy tablet. However, many parents deliberately expose their children to the chicken pox virus to allow them to become immune. In 1995 in the UK over 2000 people were killed in a road accident, over 600 people died from falling down stairs, 60 people drowned in the bath and 6 people died from dog bites. These death causes received little publicity and certainly did not have the same sort of public reaction as the tragic story of Leah Betts. It would appear that we have a natural tendency to focus our risk mitigation based on the level of publicity rather than the quantified risk.

So lets separate publicity and risk. The public response to the death of Leah Betts is to be expected, it was a shocking story. She came from a typical middle-class background, despite the loss of her mother a few years previous to the incident, she had a stable family life and all was well. This story highlighted how easy it is for a well behaved teenager, with a bright future ahead of them to make a bad decision which results in a tragic outcome.

So what was the risk of the same fate befalling your child in that year? Leah’s was the only recorded death involving ecstasy or MDMA in 1995. Since then cases have increased slightly, and the average number of UK deaths involving ecstasy since 1995 is 7.

So lets equate publicity with emotion, the publicity and public response is understandable as we are dealing with a highly emotional subject with which many people can empathise. However, the risk of a similar incident remains low. Yet, if we ask any parent today which risk they make sure their child is aware of more, the dangers of taking ecstasy or the dangers of being bitten by a dog, most would answer the same way. Yet the chances of death from either of these is pretty even.

Does this relate to the workplace? In my experience it does. I have met many health and safety managers, and they all have their own pet hates. They all have one or two hazards they really focus on when they visit a workplace. Does the risk associated with these hazards increase when they arrive on site? Of course it doesn’t, so are they focussing on risk or are they letting their emotion determine their focus?

The next question is, does this matter? If someone’s personal experience causes them to focus more on one hazard and this increases awareness of the risks associated with this hazard, then this could be a good thing. However, if increased awareness of this risk is at the expense of focus on other risks, this could be damaging. I am sure many readers remember the Texas City refinery explosion. One of the findings was that BP had shifted focus from process safety to human behaviour. A focus on human behaviour is critical to reducing accident rates, however, it should never be at the expense of other controls. This is why quantification of risk is essential and an objective view towards risk is critical in the workplace.

A colleague of mine who is a risk expert always says, people don’t die jumping out of planes, they die crossing the road. The point is, when you jump out of a plane you enter into a hazardous task with your eyes open. You have many controls in place, the risks are evident and you are focussed on them.

So don’t let emotion based decisions distract you from the real risks in your business. Report your incidents and analyse the numbers. More importantly, record, categorise and analyse your observations and near misses. These will help you focus on your business risks. If you don’t have a regular meeting where your team analyses your near miss causes and your unsafe acts and behaviours, then seriously consider introducing one.

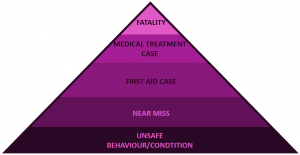

Please don’t allow yourself to be blinded by the high profile jobs, the jobs that everyone is talking about and everyone wants to be involved in. Make sure your controls for these are in place, and maintain focus on your daily tasks that present as risks indicated by your statistics. Bird’s triangle is a well known model and graphic for a reason. By focussing on the observed hazards and near misses you can avoid the major incidents and fatalities at the top. If you read about Bird’s research, you will find reference to estimates of near misses and property damage. This is simply reference to his research method and records that were typically kept at the time. In modern health and safety management, these numbers can and must be recorded based on observations if you wish to avoid major incidents. It is by analysing and addressing the root cause of these occurrences that we avoid serious injury or death in the workplace. Use consequence management to encourage reporting of such occurrences. Effective consequences are rewards such as prizes for the most observations reported or simple recognition in a team meeting for someone who has reported an unsafe act or condition and perhaps acted upon it themselves. This encourages further reporting.

Please don’t allow yourself to be blinded by the high profile jobs, the jobs that everyone is talking about and everyone wants to be involved in. Make sure your controls for these are in place, and maintain focus on your daily tasks that present as risks indicated by your statistics. Bird’s triangle is a well known model and graphic for a reason. By focussing on the observed hazards and near misses you can avoid the major incidents and fatalities at the top. If you read about Bird’s research, you will find reference to estimates of near misses and property damage. This is simply reference to his research method and records that were typically kept at the time. In modern health and safety management, these numbers can and must be recorded based on observations if you wish to avoid major incidents. It is by analysing and addressing the root cause of these occurrences that we avoid serious injury or death in the workplace. Use consequence management to encourage reporting of such occurrences. Effective consequences are rewards such as prizes for the most observations reported or simple recognition in a team meeting for someone who has reported an unsafe act or condition and perhaps acted upon it themselves. This encourages further reporting.

Tourists have been gathering at Princess Juliana beach to watch the planes land since 1943. Despite numerous injuries and falls, the fatality last week is the first ever fatality of a tourist from watching the planes. So, while the decision to hold on to the fence and grab a thrill proved to be a fatal one for this New Zealand tourist, the risk based on previous fatalities appears low. However, the frequency of near misses and unsafe occurrences may suggest that such an incident was inevitable with the existing controls in place.